A Few More Dances with the Devil

"I ain't as good as I'm going to get, but I'm better than I used to be"

Those of you who have followed this page from the beginning are aware of the challenges and tribulations that sparked me to start recording these entries and sharing my story. Over the last several months, I was afforded the opportunity to revisit many of those very issues that originally troubled me. And at times, stood toe-to-toe with some of the toughest ones yet.

Through it all, I discovered more about myself, my insecurities, my mind, and my understanding of stress. I knew that while so many things felt familiar, I couldn’t rely on past coping mechanisms to deal with them. After all, the definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again, expecting different results.

It hit me that if the same problems were resurfacing in my life, my old habits/processes to manage/overcome them probably aren’t the best tools for the job. Or maybe they were at one point, but the ever increasing complexity of the world and your interactions with it force you to evolve just to maintain a certain level of proficiency.

“No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it’s not the same river and he’s not the same man.”― Heraclitus

In March of this year I switched jobs from a role in government contracting to one at a large media/marketing agency. The change resulted in both a different environment physically for work and a contrasting approach to the intellectual stimulation I engaged in throughout the day.

Like most large corporations, the company I moved to had gone fully remote during COVID. I was onboarded in the silo of my own apartment, with minimal interaction amongst my co-workers the first few weeks. I knew what I signed up for, so I took it in stride with the expectation that in time, work would pick up, I would be keeping busy, and we would return to office under a hybrid schedule. I was excited to be out of the old world of government proposals and using my brain to solve real world problems.

Being a Strategist in marketing, I tell people that I’m in the business of human psychology. As you know, I love studying human behavior and understanding the world around me, so it would be foolish of me to conclude that the anxieties I started experiencing at the new job were indications that it wasn’t the right fit for me. As I talked about in the last article, “Live Your Truth,” there is power in finding alignment in your work/life and personality traits. It doesn’t mean you need to feel like you won the lottery every day for work, but it shouldn’t make you miserable to the point that you dread going there.

Waking up and having a more positive outlook to my day with this job shift had me feeling very grateful. The subject matter was something I had a real passion to explore as well, but the desolation from human contact brought many different dynamics to the picture that I wasn’t ready for. With each passing day, it felt harder to focus and manage my time when it seemed like I would have all day to do a few tasks. I started having negative self talk because I was mad at myself for not being disciplined and not feeling a sense of motivation to get work done. Those internal conversation with myself slowly lead to me feeling in a constant state of uncertainty. I couldn’t trust myself, I didn’t know what I was capable of, and I felt like I didn’t belong. Classic Imposter Syndrome.

From middle school through college, I consistently excelled in my academics and graduated with the highest honors. I attributed it to my discipline to limit distractions, finding times of the day to be heads down focused on work, and always staying ahead of deadlines. I notoriously had homework and papers done a week before they were due. There is value in the pressure to get work done, and performing under pressure is a great skill to have, but I never wanted to routinely rely on an external source for motivation (more to come on this later). I also thrived in the consistent feedback loop that academics provides (more on this later). The weekly agenda in college was always pretty straightforward, and professors would normally provide an outline of key dates in the semester to keep in mind on the course syllabus day one.

Not only was the calendar structured, you also reliably got performance assessments on the work you did. I understand that certain classes had different deliverables, and not every subject demanded the same workload, but one can’t deny that as a whole, the academic system in America is very feedback heavy. You always know where you stand. And if you don’t, a quick trip to the professors office can clarify that for you.

Homework, grade. Paper, grade. Presentation, grade. Test, grade. Not a whole lot of uncertainty in this system.

Now, shifting into the “real world," my day to day calendar could be very tentative. I might have a meeting come up. I might have a last second client demand. I might even be told I’m leading a presentation if a co-worker calls in sick. Many unknowns. And when I did have a meaningful tasks to complete, I didn’t necessarily get feedback from my co-workers or my boss as to how satisfied they were with my work. All this turns into a great breeding ground for uncertainty based anxieties. That mixed with my perceived lack of discipline and motivation caused me ever growing stress, not to mention the loneliness experienced with my remote work situation. The physical response to the stress then brought about more challenges that escalated what could have stayed low level stress, to crippling anxiety and panic in the isolation of my own apartment.

Doubting yourself doesn’t mean you’re going to fail. It usually means you’re facing a new challenge and you’re going to learn.” —Adam Grant

Fortunately, I stumbled upon a podcast with a Stanford neuroscience professor by the name of Andrew Huberman, who said, “If you cannot control the mind with the mind, look to the body. When we are at the extremes of the autonomic nervous system, our thoughts become a bit like a runaway train; when you’re sad or stressed it’s hard to get out of those states with thinking alone.”

That comment made me commence research and exploration into the physiological components of stress, the neurochemicals associated with stress, and more tools to manage those biological/chemical mechanisms.

The Neurology of Anxious Arousal: How Fear is Determined

In my second article, “Three Foot World” I wrote about the two stages of the response to an event/stressor. Your initial impression imposed involuntarily on you, and then the second impression in which you voluntarily add judgment of assent to that initial impression. This was written about in the context of Stoic philosophy. As I read more about anxious thinking, especially in its relation to obsessive intrusive thoughts, I was able to put scientific explanations to these philosophical concepts.

Anxiety can be defined as reacting or worrying about something quite safe as if it’s objectively dangerous. If a thought is followed by an anxious experience, the pathway from thought to fear gets established. This is not necessarily bad, as it’s evolutionarily beneficial to make connections and associations to dangerous phenomenon in your world to keep you safe and alive.

The “Alarm Response” is the first phase of responding to a potential threat. This is the classic fight, flight, or freeze phase. This signal can include the release of adrenaline, and it’s centered in the portion of the brain called the amygdala. The amygdala can be either on or off; it either triggers the alarm response or it doesn’t. It cannot decipher or react to the magnitude of the danger. It only can say yes or no, so with even the merest hint of possible danger, that bell will go off.

That bell is there to keep you safe, not comfortable. So it rather send a hundred false alarms and create moments of fear at the potential for danger (False Positive), than to miss that one moment that really was fearful and dangerous(False Negative). Those false alarms will feel like a whoosh sensation. Think of someone jumping around the corner to scare you. As you go through life you continuously program the amygdala to discern whats fearful and what’s not.

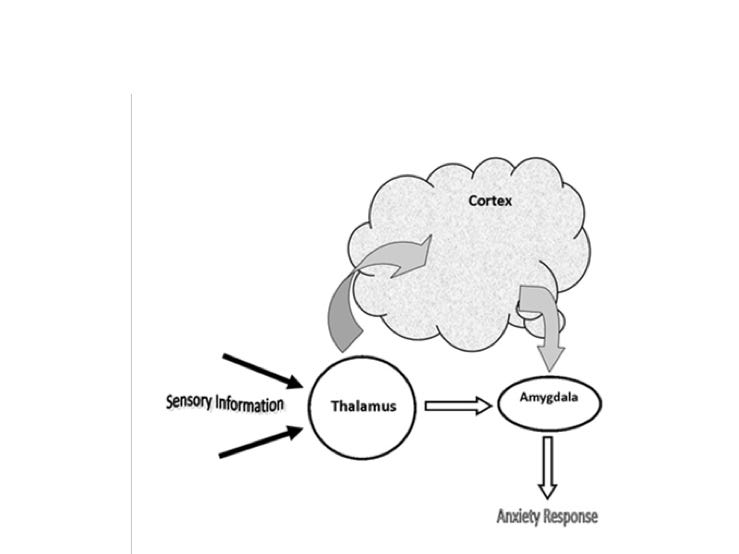

The amygdala receives two signals from the Thalamus in response to a trigger. One signal is direct and extremely fast. The other is sent a slower route through the Cortex of the brain (the part of the brain responsible for memory, thinking, learning, reasoning, problem-solving, emotions, consciousness) which then helps to determine whether the trigger is a threat or not. The Cortex message arrives to the amygdala a half second later than the direct signal, but that delay carries the information on whether to keep sounding the alarm or to let the first fear fade.

The big takeaway here is that first fear signals are unavoidable. Willpower has nothing to do with it because it is triggered before willpower has a chance to intervene. It’s up to the Cortex encoded signal that arrives a half second later to have a formal response to the trigger. When that formal response is corrupted or distorted, that’s when panic and escalation of fear take over. The world seems different when your amygdala has triggered/keeps triggering the alarm response.

Understanding how your perceptions of reality are altered in an alarm state can then help you identify when you need to potentially turn to the body to reduce the alarm bells. It’s hard to take you mind off the feelings of anxiety, and when you’re in an anxious state, your sense of time becomes compromised. The current anxious state feels as if it will go on forever. This is interesting because the same is not true when we are in a happy state. Many times the happy state almost goes unnoticed, and we don’t think about it in relation to time.

When you are at the extreme ends of the stress system, you need to be aware that your mind is not your best friend, and that better conscious decisions can/will be easier to entertain if your autonomic arousal goes down.

What is that Anxious Feeling

As complex as the human body is, there are very rudimentary aspects to its functionality. It would be inefficient to have a totally different response to the stress of public speaking, relative to the stress of being chased by a mountain lion. Like the yes/no aspect of the amygdala, the hormones and chemical released to stress are the same regardless of the stressor itself. The hypothalamus of the brain will send signals to the adrenal glands to release adrenaline and cortisol.

Adrenaline increases your heart rate, elevates your blood pressure and boosts energy supplies. Cortisol, the primary stress hormone, increases glucose in the bloodstream, enhances your brain's use of glucose and increases the availability of substances that repair tissues. Cortisol also curbs functions that would be nonessential or harmful in a fight-or-flight situation. It alters immune system responses and suppresses the digestive system, the reproductive system and growth processes. Contrary to popular belief, stress activates your immune system. Adrenaline signals the release of killing B and T cells from the spleen, allowing you to fight fevers and sickness thats in the body. Again, the stress response is generic, not case specific. We often think that stress will cause us to get sick, but it’s the crash of the stress that leaves us susceptible to foreign pathogens.

This chain of events in the stress response is designed to put us into states of motion. Again fight or flight typically involves action. We find ourselves in discomfort because many times we have this stress response happening at a time when we are trying to remain still. Think public speaking, big conversation, final exam. Having awareness of the components to the sensations you feel go a long way in allowing you to practice equanimity with the stressor you’re experiencing.

One of the best saying I came across in my research of stress is, “What you resist, persists.” The more you concentrate on the stress response and how anxious you feel, the worse you’ll feel. If you go to a party and you make it your objective to put everyone at ease, you will probably have a great time and won’t feel anxious. But if you go to that same party with the goal of not being anxious, all you’ll think about is being anxious and you’ll have an awful time. The more self-conscious your are the more miserable you are. Self-consciousness is associated with loads on neuroticism. Making it more about others, and less about you will help alleviate this tension. And there is science to prove it.

The Role of Tachykinin

The human brain can really only focus on two things at once. Think of your brain as having two spotlights constantly going. You can point them in different directions, you can align them to the same anchor, you can dial up the intensity of one, and tone down the brightness of the other. This doesn’t really hit home until you ask someone why they turned the music down in the car to focus on finding a parking spot or a specific road to turn down. The brain is simply processing sensory information, so adjusting the spotlight connected with the music gives you the ability to focus on the visual stimuli entering your eyes better.

With that, if the spotlights are both being directed towards internal states, we will often find ourselves stressed and anxious. Stress is created by too much attention on our internal state. High performing teams and individuals realize this, and thus make an effort to help/focus on others at times when they are stressed. If you devote your attention and energy on providing for others, it takes the spotlights off your internal states, and puts you in a “forward center of mass” according to Dr. Huberman.

Nature designed humans in such a way to be social creatures. It’s in our biology. We have push-pull neurochemicals in our nervous system. When you isolate you promote the release of a neuropeptide called tachykinin. When you help others, you suppress the release of tachykinin.

Tachykinin causes stress, heightened perception of fear, low level aggression, and inhibits our immune system. On the flip side, oxytocin and serotonin are the molecules released when humans engage in pair-bonding and social endeavors. These are our pleasure hormones. Evolutionarily it makes sense for nature to want us to engage in collective behavior as it was beneficial to our survival. These systems weren’t created by pure coincidence. We can then think of tachykinin as natures punishment for isolation.

I don’t have data to back this up, but I would be willing to put money on many mental health issues that surfaced during COVID being traced back to this very rudimentary system the body has. There is a vast amount of anecdotal data that points to many individuals that commit violent acts (mass shootings/terrorist attacks) having spent a considerable amount of time alone prior to their actions.

The next time you’re stressed and you feel agitated, or compelled to move, understand that’s your nervous system giving you energy. Use that energy to help others and promote the release of your pleasure hormones, and remove the spotlights from over analyzing your internal states. Navy SEALs and other high performing military teams instill this into the fabric of their being from the beginning. They also embrace a philosophical perspective on stress that scientifically gives them and edge. They embrace the notion of a “Growth Mindset.”

The Role of Dopamine

Cultivating a Growth Mindset involves learning how to access rewards from effort and doing, as opposed to rewards for outcomes. Evoking a neurochemical response from the friction/challenge that you’re in. This is where the hormones testosterone and dopamine come into the equation. The androgens testosterone and DHT bind to receptors and activate certain components of the amygdala, which can send the signal of making effort feel good. Where the real insight lies though, is knowing that effort itself increases testosterone. Like I mentioned above, going into “forward center of mass” (responding positively to a stressor) then gives you an upper hand from a neurochemical standpoint in addressing your challenge. In the same way the stress response system is generic, the motivation system is just as generic.

The adrenaline/epinephrine released during the stress response will create a state of readiness in the body, the testosterone will make us feel good, and dopamine will put us in a mode of motivation. We call these “Pursuit Hormones".” Just for context, the molecules serotonin, oxytocin, and prolactin are considered “Pleasure Hormones.”

These two system of hormones ideally operate in oscillation. If you are constantly go, go, go you will experience burnout. And if you never engage in effort, you won’t have anything to actually feel good about.

Testosterone and dopamine have a very close relationship. When you engage in winning behavior your testosterone increases, and when you lose, your testosterone decreases. The trick here is how you frame winning and losing. When you frame winning as simply putting in effort, you will get rewarded from the motivation system for simply getting your ass in gear. If you define winning as becoming the starting quarterback for the Tampa Bay Bucs, sadly you’ll never get a release of dopamine or testosterone because no one is beating out Tom Brady.

As humans we have been conditioned to think that food gives us energy. And in many ways, it does. But our nervous system also has energy. It’s in the form of dopamine and adrenaline. These motivation systems were designed when humans were nomads and needed to be put into motion to find food to stay alive. It wasn’t the food that provided their energy, it was the motivation and pursuit of the food that gave them energy.

There are numerous stories of humans doing remarkable feats in the absence of food and water. In almost every situation, they made it a priority to engage in effort that moved the needle in short increments. Make it to the next mile. Ok make it to the next hill top. Etc. As long as it’s just outside your comfort zone, you’ll get rewarded with more energy when you make it there. To reiterate, engaging in effort has the effect of increasing testosterone and dopamine, which then help you engage in more effort. It’s a virtuous cycle at your full control.

Just keep in mind that dopamine is a non-infinite yet renewable resource. You will get spikes in dopamine, but they won’t go on forever. Eventually your dopamine will crash, and you’ll dip even below your normal baseline level. It’s in these moments that one should tap into the “Pleasure Hormone” system to allow for the “Pursuit Hormones” to regenerate and restock. After a big win, it’s hard to have the motivation to do it again for this exact reason. It’s why Olympians feel lost the day after winning a medal.

Like the stress response, dopamine plays a factor in our perception of time. Working hard at something for the sake of a reward that comes afterward can make the work more challenging and make you not want to do it. When we engage in hard work, school, or exercise, we are thinking about the end result, and thus extending the time bin over which we are analyzing and perceiving that experience. When the reward comes at the end, we end up dissociating the neural circuits of dopamine and reward that would have normally been active during the activity so we end up not enjoying that activity. The time feels slow and painful, you become less efficient, and you undermine your ability to perform.

This is where the Growth Mindset shines. The ability to access pleasure from effort is the most powerful aspect of our dopaminergic circuitry. Using internal dialogue like, “I’m not there yet, but I’m striving to get there” and “Stress can grow me” will energize you and release dopamine, making you more productive and successful. Embracing the process and effort in pursuit of a goal will always be more powerful than external stimuli like pharmaceuticals, loud music, or procrastination. Spiking dopamine before or after an endeavor takes away your ability to release dopamine from the effort itself. Dopamine also has the added benefit of converting into epinephrine, increasing our ability to focus.

You don’t have to lie to yourself but finding a way to attach the feeling of friction and effort to an internally generated reward system will do wonders for your productivity and satisfaction. If it comes to it, lie to yourself in the context of the truth that you want it to feel better and pleasureful, and the only way to do that is turning the effort into the reward. In my next article I’ll explore this notion of “Expectation Effects” more elaborately and describe the how your psychological analysis can come to fruition in physiological ways both positively and negatively.

Action Items

In the meantime, try to become intimately aware of how the stress response impacts your daily life, and the mechanism you have traditionally turned to to cope with it/grow from it. Analyze whether you’re perpetuating a first fear into an ongoing alarm bell, or if you’re allowing the reasoning portion of your brain to quell the false sense of danger the amygdala was warning you about.

If you are lacking motivation, restructure your ambitions to allow yourself to get into a battle rhythm of wins. Create little meaningful milestones throughout the day that will keep you in a state of pursuit, without making the tasks seem daunting or painful.

Understanding these neurochemical and biological systems has drastically changed my ability to manage the day-to-day ambiguities that life and my career throw at me. The panic attacks and days of mental paralysis are now fewer and farther between. Words can’t describe how much appreciating and love I have for my parents, family, friends, and community for believing in me the whole time, and keeping me hopeful of a brighter future.

Resources for Further Discovery